This is post #1 from the Idea Maze! Thank you for following along on our journey.

The central question of this newsletter is “how do founders figure out what problem to solve and what company to build?” It is rooted in the belief that highly talented entrepreneurs are the scarce resource in the startup world, and the greatest tragedy is a talented founder stuck working on the wrong thing. Nobody wants this, and this isn’t good for anyone.

The goal of this newsletter is not to share a prescriptive method for navigating the idea maze. Instead, I want to bring to light stories of how other founders have approached this journey. There may be concrete lessons learned through these experiences, but some may just be interesting stories of pure luck. I’ll try to draw out some takeaways from these interviews, but think of this newsletter as one that is mostly filled with fables as opposed to frameworks.

But first, where did the idea of this newsletter come from? This really goes back around 12 years to about 2011. I’ll share three very brief stories that all happened around the same time.

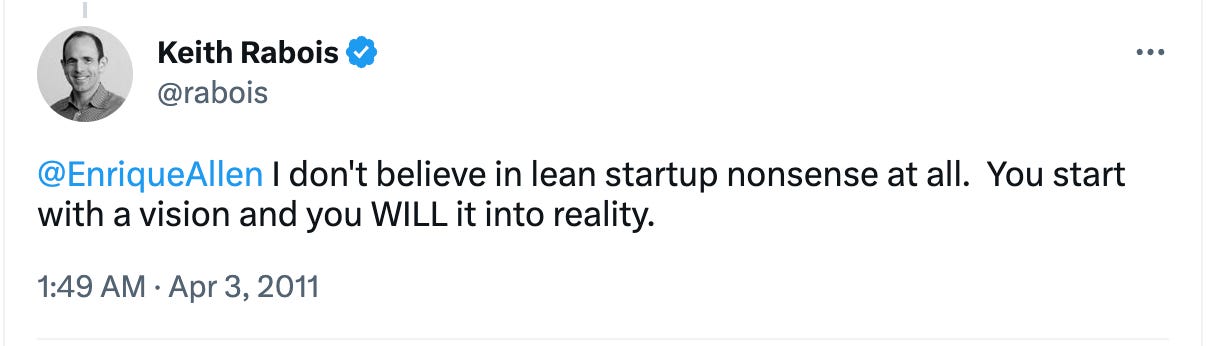

Fable #1 involves a tweet. Rewind the clock to 2011 and remember that this was peak “Lean Startup”. The techniques promoted by Eric Reis and Steve Blank was leading to much smarter and cost-efficient experimentation and validation of startup ideas. I was reading everything I could about the lean Startup Method and had a heavily dog-eared copy of “4 Steps to the Epiphany” on my bedside table.

But not everyone was as convinced.

I distinctly remember reading this tweet and stopping in my tracks. I think I had just met Keith around this time, and his track record as an angel was pretty much unparalleled. This led me to notice the ways that the Lean Startup Methodology was becoming a crutch for entrepreneurs searching for something to build. Ideas were treated frivolously. Conventional wisdom said that “the idea doesn’t really matter, because founders will end up pivoting anyway.” While this may be empirically true, it seemed highly inefficient and defeatist (and intellectually lazy).

Ok, fable #2. This was at the first or second Techcrunch Disrupt in NYC. One of the speakers on the agenda was Paul Graham (he was still running YC at the time). After some moderated Q&A, Paul was asked to do “live office hours” with a few founders that were building seed stage companies. These office hours with Paul were the stuff of YC legend, and I popped in to see how he was able to quickly cut to the heart of a startup’s problems and offer transformative, actionable feedback.

I think there were six companies that spoke with him, but I only remember one of them. After asking a series of questions about the market, problem, and product, I remember Paul pausing for a second as he considered his next words.

“It seems like you might want to start over”

Wow, that was pretty remarkable. Again, this was during peak lean startup, and so you’d expect that the advice would be more along the lines of some customer development that could illuminate the path to a fruitful pivot.

But instead, Paul suggested something pretty stark and definitive. The premise of the business was weak, so it was probably better to start again from a blank canvas.

Fable #3: This time, things hit home more directly. Around this time, we invested in two companies nearly back to back that were led by very product centric founders.

One company was in the B2B space. The founder was an experienced product leader with strong domain expertise. We loved the team and the core thesis. But something about the product approach irked us. When we would dive into specifics about the roadmap and the core features that would be important, his conviction level was surprisingly low. Instead, we heard the refrain “we know what our core principles are, but we’ll talk to our customers and they’ll tell us what is really important to build”.

The other company was in the consumer space. The founder was building a calendar application that would be called Sunrise. I can’t remember the specifics of the pitch, but it pretty much came down to “people use this product multiple times every single day, and ours will be better.” The founder was utterly convinced that his team could execute on a superior product, and that winning was less about giving customers specific features but about great design and the comprehensive experience. His insights were largely intuitive, although informed by careful observation.

Around this time, I was reading the course notes from Peter Thiel’s lectures at Stanford (which eventually become the book Zero to One) and he had introduced his framework of deterministic optimism. I remember making the comment that the first founder was surprisingly “non-deterministic” about what he wanted to build. Conversely, the second founder was extremely deterministic. Ultimately, the first company did eventually find some product market, but within a relatively narrow market segment. The second company found product/market fit quite quickly and was ultimately purchased by Microsoft for a meaningful return for all involved.

So, what are the lessons from these fables?

First, there isn’t really a framework for figuring out what to build. Techniques like Lean Startup are useful but insufficient. For more thoughts on this, check out this post.

Second, ideas matter. Of course they do! And if you are focused on the wrong thing, it might be best to start over.

Third, at some point, you need to be deterministic. If the opportunity and path forward were obvious, someone would have likely found it already.

Closing thought – if I think through the $1B+ companies in our portfolio, 75% are doing pretty much exactly what the founder set out to do. 25% are the result of essentially starting over with a new idea. Pretty interesting.

Thanks for reading this far. I promise the other posts will not be this long. But I wanted to set the stage!